Beyond the digital divide

A few days in Big Sur

Thank you so much for reading The Wilder Things. To read every post, please consider becoming a paid subscriber! $5 a month gets you every single newsletter, the ability to comment, and access to the archives. Also —if you get even just three people to subscribe, you get a discount! So smash that subscribe and share button. I am so grateful for your support.

For the first time in a long time, I had a week off from work. My husband, Tyler, met me in Vegas, where I was finishing up at NBA Summer League. From there we flew to San Jose, rented a car, and drove to Big Sur. I have always wanted to see the Redwood trees and the cliffs that drop right into the ocean.

I knew it was going to be beautiful, but I wasn’t prepared for it to be magical. I know that magical is a vague, overused word, but that’s the best way I can describe it. The air was clean and smelled like lavender and honeysuckle. I’m a pretty skeptical person, but there was something out there in the forest and the ocean that I couldn’t touch or see.

Perhaps it had something to do with the scale of the place. Even after staring at it for five days, it was still hard to comprehend the drama of the landscape. Where we stayed, the cliffs — green and yellow with fresh growth and dried-out grasses and plants — plunge into the ocean 1,200 feet below. The clouds would roll in over the water but we would stay above them, the sky blue over our heads. I kept closing my eyes, wondering if the scene would compute better when I opened them again. But every time I did, the views from atop the cliffs were almost too grand to understand.

“It’s looks like a screen-saver,” I said, and then hated that I compared something so ancient and real to a two-dimensional part of a man-made machine.

The scale of the trees was difficult to fully grasp, too. On our hikes, we’d stare up at the Redwoods that shoot straight up out of the ground. They are (obviously) massive. Each one felt like a specific living being with its own personality. Some grew in stands of five, some stood alone. Some had other trees growing out of their massive branches forty feet in the air. They can live for thousands of years.

There was something…melancholy about the trees. A few had fallen and died and were now covered with moss, turning back into soil. Some of the dead trees had other trees growing out of them. How profound to have your dead lie among your living, I thought. I wondered if it made the other trees sad, or if it was a comfort to watch them decompose back into the earth and give life to others.

When white people went west, they cut down 95% of these stoic trees, turning them into capital. The thought of cutting down even just one makes me feel nauseous.

I had a favorite tree. It had burned at some point, but Redwoods have remarkably insect- and flame-resistant bark (which is why they made such coveted material for buildings). This one managed to stay alive and seemed to be healthy.

The trunk was split open at the bottom, its bark splayed apart and hollowed out for about seven feet before growing back together. It formed a little cubby, the inside of which was coated with a layer of charcoal. I’m pretty sure I found god in there. Not capital G God, but that mysterious force that contains the unknowable answer to the central question of existence, which is, simply, why?

I’ve never heard silence as loud as it was in that hollow tree trunk. Standing outside it, I’d hear birds chirping, the wind rustling through the canopy. Then I’d step inside the charred interior of the trunk and hear absolutely nothing. Instead, I felt this light pressure, this electrical current, all over my body, the way some people describe what it feels like right before lightning strikes nearby.

Big Sur confounded me in other ways. I knew people lived there, I just couldn’t see any houses. A woman named Jolinda, who worked at the restaurant of the inn where we stayed, told us there’s an ordinance mandating that all residences must not be visible from Highway 1. Jolinda lives up in a canyon, three miles off the highway, which is the only road that cuts along that part of the coast. Her road is so bumpy, she said, that it takes thirty minutes to make it to her house. There’s very little cell service up there, and she says she often misses calls from friends and family back home in Kansas.

“I try to explain to them,” she said, “That out here we live beyond the digital divide.”

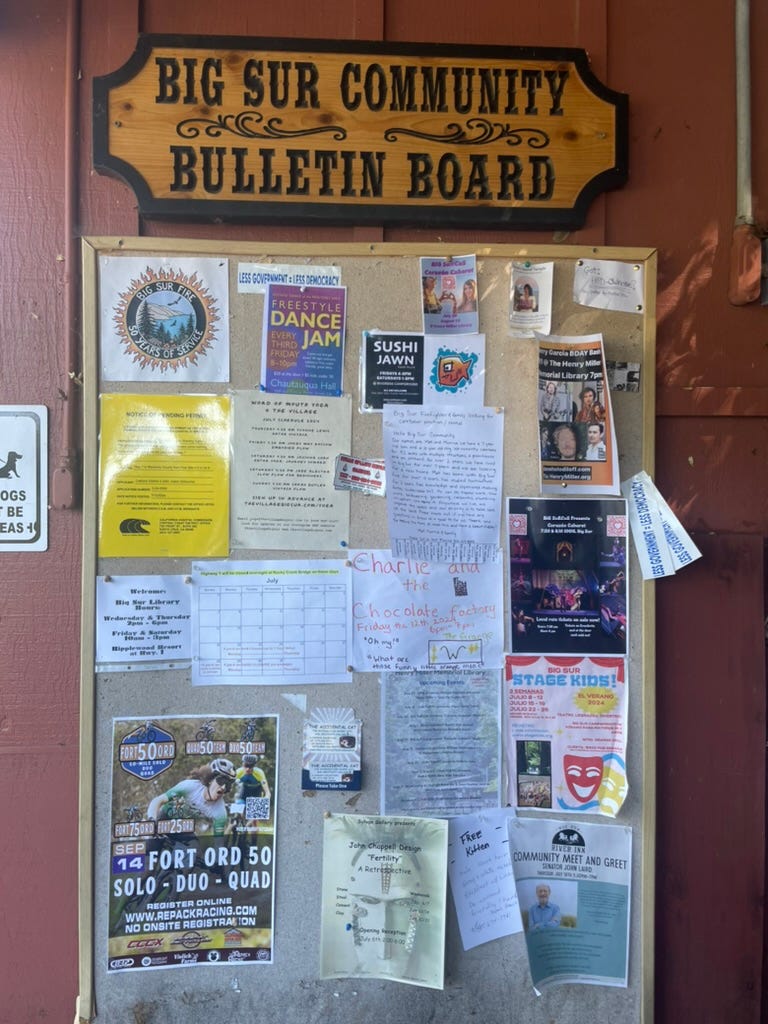

On our last day, Tyler and I drove around and took film photos of our favorite places. We stopped by The Big Sur Deli, which is in the same building as The Taphouse, one of two bars that locals go to. I know this because Joseph told us so. Joseph was a local who saw me taking a picture of the community billboard hanging on the outside of the building and asked, “What are you taking a picture of this for?”

I wasn’t totally sure. But I told him I wanted to read all of the fliers, and there were so many that I didn’t have time to stand there and take them all in.

“That’s fair,” Joseph said, smiling. He had long hair and dirt all over his clothes, because he’d just picked 150 pounds of plums from a rich person’s private orchard. They were being donated to something called The Big Share, a farmers market where residents can come get free, fresh food.

“People don’t realize, it’s a food desert around here,” Joseph said. “To get groceries, you have to go up to Carmel, and that’s at least a three-hour round trip. Families who work don’t have that kind of time.”

Joseph peered at the board. There was a calendar that marked off when certain bridges along Highway 1 would be closed for repair. One of them was actively collapsing, Joseph told us, so road workers were closing it off for three days next week. The bartender inside was worried, because he lived on the other side and wouldn’t be able to get to work. But Joseph said they’re used to dealing with inconveniences and disasters, from landslides to creeks flooding to disruptive maintenance. The community was very close; they all took care of each other. The bartender would sleep on someone’s couch.

“I don’t even have some of my best friends’ phone numbers,” Joseph said. “I just go find them. There are only so many places they can be — either here or at Fernwood.”

“Are people less lonely here than in the rest of the country?” I asked Joseph.

“Yes,” Joseph said. “I think they are.”

There’s also no anonymity, he explained. You can’t just sit at a bar and people watch, or blend into a crowd in a city and be nobody. Sergio, another man we became friendly with, put it another way.

“There’s no crime here,” he said, laughing. “You do something bad, and everyone will immediately know who it was.”

I know that living in Big Sur is much more complicated than I could ever understand from a lovely vacation. I can’t, however, help but admire the accountability we heard about. Because while a close community is an obvious necessity in remote areas, it’s equally as vital in bustling ones, too. Ironically, it’s easier to turn inward in a highly populated place, where most problems can be solved through impersonal apps or digital communication.

There is something profound — sacred, even — about showing up in person, casually dropping by, checking in on people. I wish that sense of community were easier to come by these days in places where survival doesn’t depend on it anymore.

I hope we can go back to Big Sur someday. There’s a tree I have to check on beyond the digital divide.

I love this! I also enjoy your sports stuff but maybe do more of this, too! (No pressure tho😜)

Really lovely essay, Char! Personal and from the heart. And these people in Big Sur are probably happier and healthier than most of us living “on the grid.”